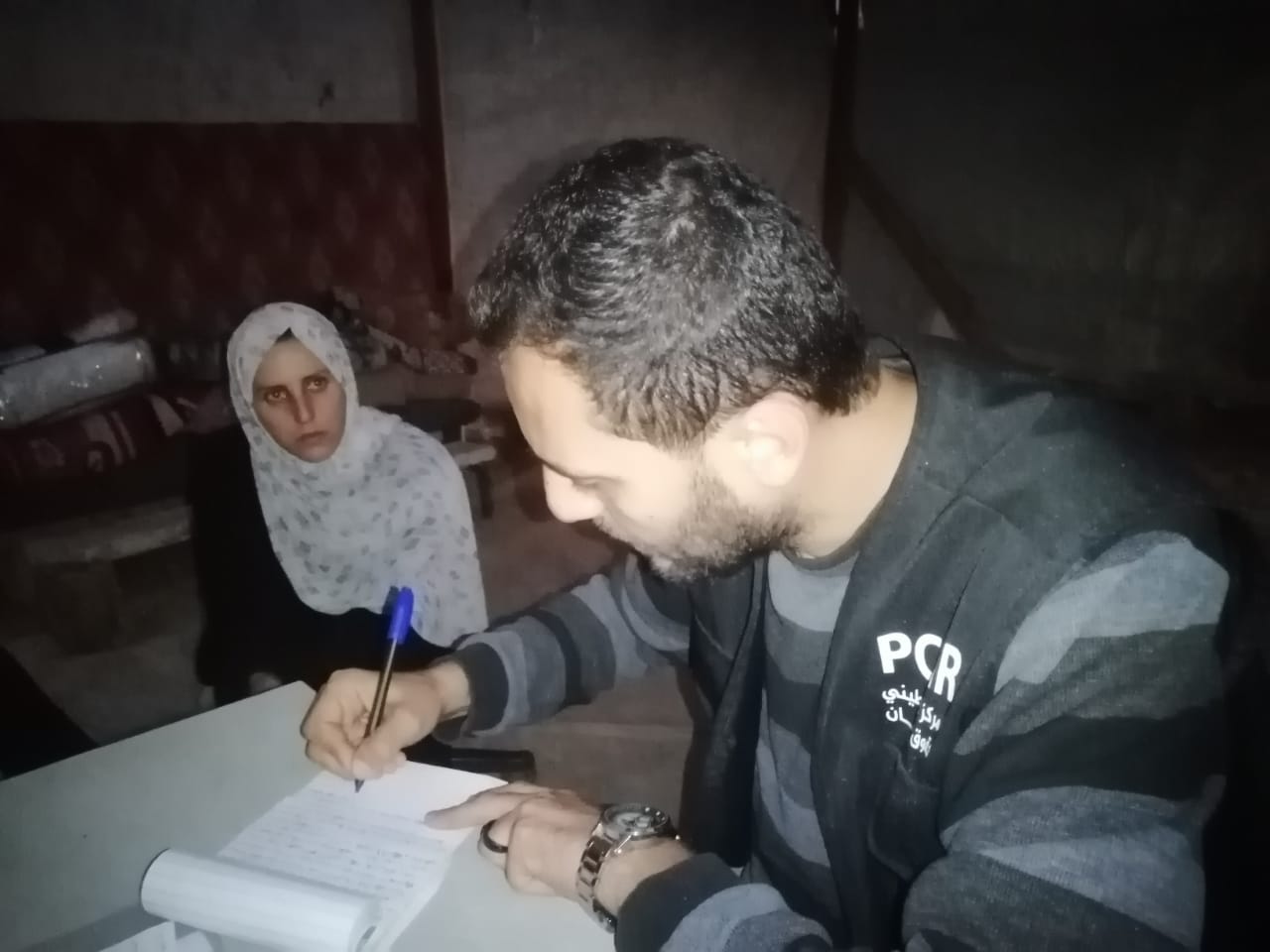

Testimony Date: 26 November 2025

My name is Jamila Khaled Mohammed Al-Marishi, 30 years old, married. I lived in Beit Hanoun in the northern Gaza Strip before harsh circumstances forced us to flee to Al-Zawaida, where I currently reside in Al-Ata’a and Al-Mahabba Camp. I hold a diploma in medical secretarial studies. Like thousands of women, I found myself facing an entirely new life after the war and forced displacement.

Before 7 October 2023, I lived with my family of six: my husband Thaer Atta Mousa Al-Za’anin, and our four children—Ali (9), Omar (8), Laith (4), and my daughter Tulin (7 months). I am now also the mother of an infant, Sanad, who is 42 days old, born on 16 October 2025. We lived in an apartment within a three-storey building in Beit Hanoun, at the Sabka intersection, leading a simple and stable life as we always had.

On the morning of Saturday, 7 October 2023, we woke to the sudden sound of violent explosions shaking the area. At 6:30 a.m., I was preparing my children for school, but as the situation escalated, we immediately abandoned the idea of sending them out. We stayed inside the apartment, following the news and trying to understand what was happening. As time passed, fear and anxiety for our children intensified, and we witnessed with our own eyes how rapidly and terrifyingly events were escalating.

That same day, the Israeli army began launching intense airstrikes and carpet bombing around the area—scenes we had never experienced before. As the danger intensified, remaining at home became nearly impossible. At noon on Sunday, 8 October 2023, we were forced to go out to the main street without any clear destination. We stood there for long hours, lost, carrying our children and not knowing where we would spend the night. I contacted my uncle Salman so we could stay with him, and we moved to the home of my uncle Amjad Salman near Beit Lahia Youth Club. However, the situation there also deteriorated. After a few hours, my husband’s family arrived and took us by car to my sister-in-law’s family home in Al-Nuseirat, while my husband remained alone in Beit Hanoun. Our contact with him was cut off due to the collapse of communication networks.

My children and I stayed in Al-Nuseirat for about ten days. During that period, my daughter Tulin’s health deteriorated severely. She began suffering from continuous diarrhoea and vomiting. I carried her from one hospital to another in search of treatment, but no effective care was provided. Her condition continued to worsen before my eyes, and I was completely helpless.

On 19 October 2023, despite all the risks, I had no choice but to return north to reunite with my husband, who was displaced at Kuwait School near the Indonesian Hospital with his maternal relatives. I stayed there with him for about a month and a half, under extremely harsh humanitarian conditions that no family could endure.

On the night of 21 November 2023, I lived through one of the most difficult moments of my life. Shells were falling without pause: artillery fire, smoke bombs, successive explosions, and missiles from Israeli warplanes. Gunfire was approaching the school where we were sheltering, and we heard my husband’s relatives saying that the Israeli army was about to storm the Indonesian Hospital. The sounds of gunfire never stopped for a single moment. That night remains etched in my memory with all its terror and fear.

We were inside one of the classrooms at Kuwait School, which was overcrowded with around fifty displaced people, adults and children, all trying to find a moment of safety. Suddenly, the Israeli army began firing directly at the classrooms, deliberately targeting the lights, plunging the place into complete darkness. We could see nothing except red and green laser beams piercing the windows and walls, and we could hear bullets flying around us. My children clung to me, sheltering beneath my legs in sheer terror.

I placed my children beside me and tried to move toward the door, but danger surrounded us from every direction. We all lay flat on the ground, covering ourselves with whatever blankets we could find. My daughter Tulin, may God have mercy on her, was asleep in my arms beside her siblings. Despite the horror, I was afraid even to hold her tightly, fearing I might hurt her.

Within seconds, an Israeli tank fired a shell directly at the classroom we were sheltering in, followed by a second shell. Screams erupted, smoke spread, and a suffocating smell filled the air, making it hard to breathe. I felt the ground shake beneath us, as if the entire world were collapsing on our heads. The blast pressure violently forced Tulin out of my arms, and to this day I do not know how she suddenly disappeared from my arms.

I began pushing debris off my children, screaming, “Ali! Omar!” The ground was covered with rubble, glass, and destruction. People were screaming in every direction, and darkness enveloped the place. I asked Ali and Omar to search calmly for their sister, repeating: “Where is the baby? Look for her carefully… don’t step on her.”

As I searched, I saw a faint light coming from an opening beneath the partition wall separating the women and men. A young man was lighting the area with his phone flashlight, asking if anyone was still alive, while in the background I heard other men warning of the possible explosion of gas cylinders.

At times I crawled; at other times I stood up, only to fall again amid the chaos and destruction. My body was in pain, and I began to feel a burning sensation in my leg. Later, I discovered that four shrapnel fragments had lodged in my leg, that my son Ali had been injured in his left foot to the point that the skin was torn, and that Omar had been struck by shrapnel in his buttocks. To this day, we have not been able to undergo imaging or remove the shrapnel from our bodies.

During my search, I saw Ibtisam, the wife of my husband’s uncle, lying on the ground at the classroom door, bleeding and struggling to breathe. She was taken to hospital, where she remained in intensive care for three days before passing away. May God have mercy on her.

At that moment, I put my hand on my head and realised that my head covering (the sidal) had been blown off by the explosion. I saw it lying on Ibtisam’s body, took it quickly, and covered my head, still in a state of shock and fear.

I screamed at the top of my lungs searching for my husband: “Thaer! Thaer!” but received no answer. I asked those around me if anyone had seen him, but everyone was terrified, trying to flee by any means, unable to help or respond.

When I lost hope of finding my husband among the crowd, I returned to the classroom to search through the smoke and rubble. As soon as I entered, fire and smoke rushed toward my face, and I heard the sound of a man groaning—the sound of someone dying. That sound still haunts me to this day.

I screamed loudly, calling out: “Ali! Omar!” but there was no response. All I could hear were successive explosions, gunfire from all directions, the sounds of aircraft and tanks, and clashes encircling the Indonesian Hospital. I felt myself losing control, losing my children and husband in seconds. I descended to the ground floor completely helpless, my heart collapsing with every step.

Suddenly, I saw my son Omar running toward me from the courtyard, crying. I held him tightly and asked, “My soul, Omar… where is your brother Ali?” Fear prevented him from speaking; his crying intensified, and so did my breakdown.

The scene was like the end of the world—like a Day of Judgment: blood, smoke, screams, and bodies I could not even look at.

To this day, I have not seen my daughter Tulin, may God have mercy on her. I did not say goodbye to her; I did not touch her one last time. Whenever I think of her, my heart trembles at the thought that she may have melted beneath the fire and rubble.

After a few minutes, my husband Thaer appeared—shocked, breathless. He said the strike had hit the classroom we were in and that he thought everyone had been killed. He had been with his uncles performing ablution when the shelling occurred.

I asked him, “Where were you, Thaer?” Then I felt sharp pain in my leg and saw blood flowing from a visible crater caused by shrapnel. Later, I learned that I had sustained three shrapnel wounds in my right leg—two in the thigh and one below the knee—and one fragment in my left leg.

Trembling, I said to him, “Go, Thaer… bring Ali and Tulin. They’re still in the classroom. I can’t get to them.” At that moment, my husband collapsed, sat on the ground crying, and said in a broken voice, “I can’t… I don’t know what to do. Go with the people—see where they’re heading and follow them.” I said, “Thaer, I’m injured… my leg hurts.” He replied, “When you reach Hamad School, there’s a medical point—they’ll help you with first aid.”

I reached Hamad School with great difficulty, bleeding, but no one attended to me because the cases arriving were extremely severe—amputations, deep wounds, people barely alive.

After some time, a nurse gave me a medical bandage and told me to tie it tightly to stop the bleeding. I did so despite the excruciating pain.

We remained at Hamad School until the next morning. When the sun rose, we realised that we had lost Ali and Tulin. We had no information about them. Shortly thereafter, a kind man called out to us, saying, “I saw your son Ali… he’s alive.” He was a neighbour who knew Ali well.

When Ali was brought back to us, he was injured and crying. I held him, feeling my heart shatter from the pain. I told my husband, “We must leave here immediately.” He replied, “Wait a bit… let’s see who from the family is still alive.” I insisted, “Thaer, the place is dangerous. We have to leave now.”

The next morning, as we were leaving Hamad School, the Israeli army fired a shell directly at us. We survived by a miracle. Seconds later, a second shell struck a car loaded with civilians and their belongings. The car exploded completely, killing everyone inside instantly. We saw blood erupt before our eyes—a scene that will never leave my heart.

We walked with great difficulty. I was injured, and Ali could not walk due to his wound. Suddenly, an Israeli drone fired a missile about five metres in front of us. It did not explode, but it created a large crater. The ground around us was covered with blood, rubble, and shattered glass, and we walked barefoot over it all—the pain in our feet and wounds, and the greater pain in our chests.

When Kuwait School was demolished by Israeli military vehicles, we left with nothing—only the clothes we were wearing. No bags, no blankets, no water—nothing. We walked through an area engulfed in fire and destruction as the Israeli army stormed the Indonesian Hospital under heavy fire and advanced toward Jabalia Camp.

After that night, we were displaced to Al-Zaytoun School in Jabalia Camp, where we stayed for three days without any basic necessities—no tents, no bedding, nothing. We all slept in a ground-floor corridor. Some people took pity on us and gave us two mattresses and blankets. Five of us slept on just two mattresses. Whenever someone passed through the corridor, they would unintentionally step on my injured leg, and I endured the pain in silence.

Israeli artillery and airstrikes were extremely close to the school, and shrapnel fell into its courtyard, as if death were chasing us from one place to another. We did not feel a single moment of safety.

During the first truce in November 2023, while we were still at Al-Zaytoun School, my husband said, “Jamila, the army will storm the school… the situation is dangerous, and all of Jabalia is under attack.” I could not move. I told him, “I can’t leave… my family is near Abu Rashid Pond, and my heart is tied to my daughter Tulin. I want to stay close to her.”

Our conversation was painful. My husband tried to convince me out of fear for our lives, while I clung to everything I had lost—especially my child. After hours, some young men volunteered to go to Kuwait School—the site where we were targeted—to retrieve the bodies and bury them in Jabalia Cemetery.

The sight of the bodies is unforgettable. All the bodies were placed in a single bag. Among them was the body of my daughter Tulin, may God have mercy on her, along with thirteen martyrs from my husband’s maternal family: Falah Al-Bisyouni and his son Ahmad; Attaya Al-Bisyouni and his wife Ibtisam; Atiya Al-Bisyouni; my husband’s uncle’s wife Manal Al-Madhoun and her children Mohammad, Laila, and Yahya Al-Bisyouni; my daughter Tulin, 7 months old; my husband’s aunt Kifaya Al-Bisyouni; his aunt Shatha Al-Bisyouni; and Walid Al-Nono.

All of them were killed in the horrific massacre at Kuwait School. As for me and my children, we were the only ones to survive from the classroom targeted by Israeli tanks, while the injured children were sent to Türkiye for treatment.

My daughter Tulin, may God have mercy on her, came after years of waiting and hope. I followed my pregnancy carefully and awaited her eagerly. I dreamed of raising her in my arms and nurturing her with tenderness. But God chose her as a martyr—an angel among the birds of Paradise.

On 5 December 2023, we decided to flee south on foot via the Salah al-Din Street checkpoint (“Al-Hallaba”). It was a terrifying scene: Israeli soldiers lying prone on the ground, aiming their weapons at us. After a long journey, we reached the entrance to Al-Nuseirat, where my husband’s brothers Mousa and Fadi joined us and took us south to Shafa Amr School in the Al-Janina neighbourhood of Rafah.

We stayed in a classroom—eight families in one room, with no privacy or comfort. After just one week, my temperature rose dangerously due to the shrapnel still lodged in my body, and infections appeared in my wound, with pus discharging from it.

I went to Kuwait Hospital, where I finally received treatment and improved slightly. I cared for my wound daily, but my mental state was completely shattered. The psychological pressure shook me to the point that I sometimes acted violently in the classroom, breaking things unconsciously. At night, I screamed from the pain and rubbed my leg intensely. Nightmares haunted me every night.

Life at the school was pure suffering: no privacy, scarce water, almost non-existent basic services, and long waits for toilets that were themselves a form of torture. Aid was extremely limited and insufficient to ease anyone’s pain.

As the assault on Rafah approached, conditions worsened daily. Bombing was random and continuous; smoke bombs were dropped around the school; people began to leave gradually until only us and a few families remained. We felt fear and isolation. We found no transportation to a safe place, and even if we had, we had no money to pay. My husband was unemployed with no income; our financial situation was below zero.

My family in the north tried to help as much as they could, sending small amounts of money despite their own hunger and hardship. Still, we could not find a suitable place to shelter amid the constant displacement.

On 6 May 2024, a friend of one of my brothers-in-law contacted my husband and informed him of a plot of land where we could stay temporarily until the war ended. We went to Al-Zawaida, where we spent the first night outdoors, under trees, without cover, in severe cold. The next morning, young men set up tents—one for women and one for men—and we began trying to organise our lives despite the harshness.

With the start of the second truce in January 2025, I returned north to Beit Hanoun and stayed with my sisters for twenty days. My husband then prepared a tent next to the ruins of our destroyed home. On the first day of Ramadan, I joined him, and we stayed there for about seven days. During that time, the Israeli army fired randomly, even during the truce. I was exposed to a dangerous incident while washing dishes when an Israeli soldier fired at a stone near me, shattering it and sending fragments into my leg. For a moment, I thought I had been hit. I told my husband, “Let’s leave Beit Hanoun… the situation is very dangerous,” but he refused.

That same night, the Israeli army violated the truce again, launching intense gunfire, carpet bombing, and artillery shelling. I felt that the war had never stopped and that every so-called “truce” was merely words.

We stayed only two days in Beit Hanoun. On 18 March 2025, we were forced to flee on foot with nothing, leaving everything behind. We headed to an UNRWA school near Abu Rashid Pond in Jabalia Camp, where we stayed for nearly two months, until May 2025, when the Israeli army invaded Jabalia and ordered a complete evacuation.

We were displaced again, this time to Al-Nasr neighbourhood in Gaza City, where we set up a tent on the roof of a house previously bombed by warplanes. The place was surrounded by rubble, infested with insects and rodents, with no protective barrier or sense of safety. Our conditions deteriorated day by day.

During the famine, my husband had no work or income, so he was forced to go to so-called “aid distribution sites—death traps” in the Zikim area in northern Gaza to obtain a sack of flour. Sometimes he returned with a sack; other times, with nothing. He faced real danger as the Israeli army fired on people gathered there. Still, he risked his life for us, as we could not afford to buy flour or even secure basic provisions.

During this period, I was seven months pregnant and needed nutrition and medical care, but I could not receive regular follow-up due to economic collapse, lack of safety, and constant displacement. Even when treatment was available, it was expensive, and most essential medicines were unavailable—fish oil, calcium, iron. The only thing I received was some vitamins from UNRWA. With constant movement, I did not know where medical points were located. My life and pregnancy grew harder each day.

On 18 September 2025, while we were living through terrifying days, the Israeli army was bombing house after house in Al-Nasr and Al-Shati Camp. Evacuation threats continued relentlessly. We saw an evacuation notice on social media directing residents to head south, and we realised that staying had become a real danger.

We were forced to leave everything and flee toward Al-Zawaida. We did not even have transportation fare, but God made it possible for someone to help us, and we shared the cost with two other families. It felt like a door of relief opening amid hardship.

The journey from Gaza City to Al-Zawaida took more than eight hours due to massive traffic on Al-Rashid coastal road. Thousands of people were walking in the same direction, each carrying their pain and fear on their shoulders, as if all of Gaza were fleeing toward an unknown fate.

When we arrived in Al-Zawaida, we felt a relative sense of calm—a brief stop to catch our breath after dark days. Young men helped organise the tents, leaving spaces between them to allow some privacy. Water was relatively available: a drinking water truck arrived every two days, and water for daily use was supplied through an underground line. Men built a clay oven for baking, and we relied on a communal kitchen (takiyya) for most meals.

Despite all the pain and loss, life continued—only as much as we could bear.

On 16 October 2025, I gave birth at Al-Awda Hospital in Al-Nuseirat at 12:00 noon. I left the hospital the same day at 5:30 p.m. When I began changing my baby’s clothes and examining him, I noticed a small hole on the left side of his neck. I did not understand what it was and continued to monitor him.

A few days later, during breastfeeding, the hole swelled and began to discharge fluid. With every feeding, milk came out of the opening, increasing my fear. After a few days, I noticed a greenish substance on his shirt. When I touched the area, I felt a fatty sac filled with pus-like material. My husband immediately drained and cleaned it, and we went straight to Al-Awda Hospital to see a surgeon.

The doctor was surprised and said such discharge was unusual. He conducted examinations and imaging and reassured us slightly, but said: “At present, we cannot perform any procedure before the baby reaches six months of age.” We then went to Al-Aqsa Martyrs Hospital in Deir al-Balah, where doctors told us the condition might be a fistula. I asked the doctor to explain its meaning and cause. He said it was located in the child’s chest and had not closed properly, possibly due to incomplete development caused by malnutrition during pregnancy as a result of the harsh conditions and famine. Some doctors said such a fistula could be connected to the lungs or respiratory system or linked to a specific part of the body, but they could not determine the exact cause, which only increased my fear for my child.

Today, I feel no optimism that the war will end. I live in constant fear, feeling that everything could collapse at any moment. Every sound of a missile or explosion takes me back to the nights when I lost safety and loved ones. My heart tightens every time I remember what we went through, and fear continues to accompany me in my tent and everywhere we have been displaced.

I feel helpless to protect my children or secure a safe future for them. We lost everything: my home, my children’s safety, and the dearest thing I owned—my daughter Tulin. What was her fault? She was killed by shelling, and we could not protect her despite everything we tried.

We lived under fire, surrounded by missiles, with fear filling our hearts.

I call on the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights to convey my voice to the world. We deserve to live in peace, and our children have the right to safety like any other child in the world.

Despite all the pain, loss, and destruction I have endured, I still try to cling to a glimmer of hope—for my children and for all those we have lost. I hope the world hears our voices and stands with us in defending our lives and dignity.

I have been suffering from Herpes for the past 1 years and 8 months, and ever since then I have been taking series of treatment but there was no improvement until I came across testimonies of Dr. Silver on how he has been curing different people from different diseases all over the world, then I contacted him as well. After our conversation he sent me the medicine which I took according to his instructions. When I was done taking the herbal medicine I went for a medical checkup and to my greatest surprise I was cured from Herpes. My heart is so filled with joy. If you are suffering from Herpes or any other disease you can contact Dr. Silver today on this Email address: drsilverhealingtemple@gmail.com

FRESH FULLZ UPDATED-2026 AVAILABLE

USA UK CANADA GERMANY SPAIN ITALY AUSTRALIA

Tax Return 2026 Filling Fullz

Children Fullz 2011-2023

Young & Old Age Fullz 1930-2009

High Credit Score 700+ Scores

DL & ID Photos Front Back with selfie

DL Photos available all countries

Passport Photos

W-2 Forms with DL Photo (2021-22-23)

USA LLC Docs with DL & SSN

USA-> Name SSN DOB DL Address City State Zip Phone Email Employee & Bank Info

UK-> Name NIN DOB DL Address City State Postcode MMN Account number Sort Code

Canada-> Name SIN DOB DL Address City State Zip Phone MMN

Many Other Countries Fresh Fullz available in Bulk quantity

All Info will be provided with guarantee

Tax Filling Tools & Tutorials available

Our Team Is working 24/7 & here we’re:

————————————–

Telegram@killhacks – @ leadsupplier

What’s App – (+1) 727”’788”’6129

Telegram Channel – t.me/leadsproviderworldwide

Discord – @ leads.seller

VK Messenger – @ leadsupplier

Signal – @ killhacks.90

Email – hacksp007 at gmail dot com

Zangi – 17-7369-4210

Email Leads & phone number Leads

Crypto, Forex, Investors Leads

Payday & Loan Leads

Doctors Database, Health & Medical Leads

Car Database with Reg Numbers

Email & Pass Combos

Office365 Leads & Logins

Crypto Exchanges Leads

LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram Leads

Education & School Leads

TOOLS & TUTORIALS AVAILABLE

H@cking Sp@mming C@rding Sc@M Pages Scripting Tools

Complete packages for Sp@mming & Ph!shing Attack

Sqli Injectors & Pen3tratrion Tools with tutorials

SMTP Linux Root & Sc@m Page Scripting

C@rding Tools & Tutorials (For CC|CVV Cash out & Dumps)

We are also providing complete packages for the above listed stuff

Complete guidance & assistance will be provided

Just try our services, we’ll give your best

#fullz #usafullz #canadafullz #ukfullz #taxreturn2026 #usataxreturn #dlphotos

#personalID #leads #taxfillingfullz #usataxfilling #childrenfullz #trumpiran #indiarussia

#chinausa #usachina #MAGA #Btc #btcbullrun #cryptocrash #cryptobill #eth #altseason

*Be aware from the scammers using our cloned names

Hello my name is Kallya from USA i want to tell the world about the great and mighty spell caster called Priest Ade my husband was cheating on me and no longer committed to me and our kids when i asked him what the problem was he told me he has fell out of love for me and wanted a divorce i was so heart broken i cried all day and night but he left home i was looking for something online when i saw an article how the great and powerful Priest Ade have helped so many in similar situation like mine he email address was there so i sent him an email telling him about my problem he told me he shall return back to me within 24hrs i did everything he asked me to do the nest day to my greatest surprise my husband came back home and was crying and begging for me to forgive and accept him back he can also help you contact ancientspiritspellcast@gmail.com

Website ancientspellcast.wordpress.com WhatsApp: +2347070518515

DR UYI has done it for me, His predictions are 100% correct, He is real and can perform miracles with his spell. I am overwhelmed because I just won 336,000, 000 million Euro from a lottery jackpot game with the lottery number DR UYI gave me. I contacted DR UYI for help to win a lottery via Facebook Page DR UYI, he told me that a spell was required to be casted so that he can predict my winning, I provided his requirements for casting the spell and after casting the spell he gave the lottery numbers, I played and won 336,000,00 euros. How can I thank this man enough? His spell is real and like a God on Earth. Thank you for changing my life with your lottery winning numbers. Do you need help to win a lottery too? contact Dr UYI via drzukalottospelltemple@gmail.com OR WhatsApp on +17174154115

I was able to catch my cheating wife red handed with a man she has been having a love affair with and this was made possible by 5ISPYHAK that I met online about his good and professional services. I started getting suspicious of my wife since she became too possessive of her phone which wasn’t the way she did prior before now. She used to be very carefree when it comes to her phone. but now she becomes obsessed and overtly possessive. I knew something was wrong somewhere which was why i did my search for a professional hacker online and contacted the hacker for help so he could penetrate her phone remotely and grant me access to her phones operating system, he got the job done perfectly without my wife knowing about it although it came quite expensive more than i thought of. I was marveled at the atrocities my wife has been committing. Apparently she is a chronic cheat and never really ended things with her ex.. contact him here at 5ISPYHAK437@GMAIL.COM

Good day friends 💓.

I’ve got unlimited access to my wife iPhone and PC and also have her activities in check thanks to this dude who is a UK Hacker by his name 5ISPYHAK I got introduced to from the AUSTRALIA who helped my friend boost her credit score. His assistance really meant a lot to me. I got access to my

wife cell phone, WhatsApp calls, without her knowledge with just her cell phone number this badass did everything remotely, I don’t know. If it’s right to post his contact but I promised him referrals, a lot of fake ass out here, also someone might need his help so well. I’m grateful to 5ISPYHAK.

Good work always speak for itself, you should contact him!

Email 5ISPYHAK437@GMAIL.COM

I’m truly grateful to 5ISPYHAK for their professionalism and support during a very difficult time in my relationship. They provided expert guidance and digital investigation assistance that helped me uncover the truth I needed to move forward with clarity and confidence.

Communication was clear, timely, and respectful, and the entire process was handled discreetly. Thanks to their help, I was able to confirm my suspicions and make informed decisions about my future.

If you’re dealing with trust issues or need reliable digital investigative support, I highly recommend

5ISPYHAK437@GMAIL.COM

Did you know that there are professional private investigators who can assist you in gathering information about your partner and the texts/calls as well as deleted messages incase he/she tries to act smart to delete them. This can help you towards your divorce process which the lawyer will need. Contact 5ISPYHAK. They can provide services such as tracking their location through live GPS, monitoring text messages, WhatsApp, Snapchat, and even recovering deleted messages and address any concerns.” All these is done without any traces. He will show you the process of how he will HACK, and grant you access to SPY on their phone. The best part of his service is how simple the apps works.

Email 5ispyhak437@gmail.com

Dear 5ISPYHAK,

I am writing to sincerely express my appreciation for your support and assistance during a very difficult time in my life. Your professionalism, patience, and dedication helped me uncover the truth I needed, which gave me clarity and peace of mind.

Although the experience was emotionally challenging, your guidance and effort made the process easier to handle. I truly appreciate the time you took to help me understand my situation and move forward with confidence.

Thank you once again for your support and commitment. I am grateful for your help and wish you continued success in all that you do.

Email 5ISPYHAK437@GMAIL.COM

I want to sincerely recommend 5ISPYHAK for their professional support and guidance during a very difficult time in my life.

When I was struggling with trust issues in my relationship, they provided helpful digital assistance and clear explanations that helped me uncover the truth I needed to move forward. Their communication was patient, respectful, and supportive throughout the process.

Thanks to their help, I was able to gain clarity and make informed decisions about my relationship. I truly appreciate their professionalism and commitment to helping clients find answers.

If you need reliable digital investigation support or expert guidance, I recommend reaching out to 5ISPYHAK.

Email 5ISPYHAK437@GMAIL.COM

What stood out most about 5ISPYHAK was their professionalism, discretion, and commitment to helping me understand the situation clearly. They handled everything with respect and sensitivity, knowing how painful such situations can be. Through their expertise and attention to detail, I was finally able to confirm my suspicions and make informed decisions about my life.

Thanks to their help, I no longer live in doubt or confusion. While the truth was painful, it was also freeing, and I am grateful for the support I received throughout the process. I truly appreciate the effort, patience, and seriousness with which they handled my case.

I would describe 5ISPYHAK as reliable, responsive, and supportive, especially for anyone seeking clarity and truth in challenging personal situations.

Email 5ISPYHAK437@GMAIL.COM

Sometimes last month my Wife started misbehaving and acting weird she’s clingy with her mobile devices which made me develop a suspicious mindset towards her phone activities so I became curious to know what she’s been doing on her phone lately I searched the internet for the best and most efficient phone spying expert I found 5ISPYHAK, through twitter reviews from a trusted and verified user so I decided to give this tech genius a try to know if she can truly help me in my case. Fortunately for me, it was the right step and the best decision. I reached out to her via her contact address at Email 5ISPYHAK437@GMAIL COM and told her about my situation and she promised to deliver a satisfactory service in the shortest time possible which she did. I hired her and within a few minutes all information from her phone and internet activities popped in and it was as if I got her phone in my palm.

EMAIL

5ISPYHAK437@GMAIL COM

No one deserves to be cheated on, especially when your full loyalty lies with the betrayer of your trust. Initially, I thought I was just feeling insecure when my wife would just be on her phone at odd hours, until I decided to take a chance to know, knowing is better than self doubts and it was exactly what happened when I employed the services of this particular group I came across by chance to help check his phone out in total. Now I know when she’s telling the truth and how to curtail her, I think it is not a drastic step if it’ll make you feel better. My life got better, I stopped using my precious time to bother about her indiscretions and channeled my energy positively… Reach him on his Gmail if you need his help..

5ISPYHAK437@GMAIL.COM

If you are seeking ways to confirm suspicions of infidelity in your marriage, one effective method is to remotely access your spouse’s phone without their knowledge. Engaging a professional service can enable you to monitor not only text messages in real-time but also communications on various messaging platforms such as WhatsApp. By providing the necessary phone number, you can gain access to all relevant texts, images, and social media interactions, including those from Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat. Additionally, these services often include GPS tracking features, allowing you to pinpoint your spouse’s location via Google Maps. EMAIL

5ISPYHAK437@GMAIL.COM

I was able to catch my cheating wife red handed with a man she has been having a love affair with and this was made possible by 5ISPYHAK that I met online about his good and professional services. I started getting suspicious of my wife since she became too possessive of her phone which wasn’t the way she did prior before now. She used to be very carefree when it comes to her phone. but now she becomes obsessed and overtly possessive. I knew something was wrong somewhere which was why i did my search for a professional hacker online and contacted the hacker for help so he could penetrate her phone remotely and grant me access to her phones operating system, he got the job done perfectly without my wife knowing about it although it came quite expensive more than i thought of. I was marveled at the atrocities my wife has been committing. Apparently she is a chronic cheat and never really ended things with her ex.. contact him here at

5ISPYHAK437@GMAIL.COM

Did you know that there are professional private investigators who can assist you in gathering information about your partner and the texts/calls as well as deleted messages incase he/she tries to act smart to delete them. This can help you towards your divorce process which the lawyer will need. Contact 5ISPYHAK. They can provide services such as tracking their location through live GPS, monitoring text messages, WhatsApp, Snapchat, and even recovering deleted messages and address any concerns.” All these is done without any traces. He will show you the process of how he will HACK, and grant you access to SPY on their phone. The best part of his service is how simple the apps works.

Email 5ispyhak437@gmail.com

My name is Richard Nuttall, my wife Debbie Nuttall and I are both 57 years old. WE ARE GLAD TO ANNOUNCE TO THE WORLD THAT WE WON $105,708,321 Lottery PRIZE, with the number a lottery spell caster called Dr Uyi gave us after casting his lottery spell. Dr UYI is a great seer and he is like a God on Earth that has turned our financial status for the better. He was recommended to us by a friend in my office who he helped win the Mega milliner, and as a couple, we discussed and decided to give his spell a try. We provided his requirement to cast the lottery spell and we are $105 M richer today. We have made a vow to ourselves that we will keep testifying about him. We were skeptical at first, but no protection is risky, so we tried it and we are financially stable now. Join us to appreciate this genius. Do you want to win like us? Contact him via email: drzukalottospelltemple@gmail.com OR WhatsApp on +17174154115

Hello! It is amazing how quickly Dr. Excellent brought my husband back to me.

My name is Heather Delaney. I married the love of my life Riley on 10/02/15 and we now have two beautiful girls Abby & Erin, who are conjoined twins, that were born 07/24/16. My husband left me and moved to be with another woman. I felt my life was over and my kids thought they would never see their father again. I tried to be strong just for the kids but I could not control the pains that tormented my heart, my heart was filled with sorrows and pains because I was really in love with my husband. I have tried many options but he did not come back, until i met a friend that directed me to Dr. Excellent a spell caster, who helped me to bring back my husband after 11hours. Me and my husband are living happily together again, This man is powerful, contact Dr. Excellent if you are passing through any difficulty in life or having troubles in your marriage or relationship, he is capable of making things right for you. Don’t miss out on the opportunity to work with the best spell caster.

Here his contact. Call/WhatsApp him at: +2348084273514 ”

Or email him at: Excellentspellcaster@gmail. com

Wow what a good God I am so excited to tell you all how I become a millionaire I’m a woman of faith I was reading a comment on google where I meet a man sharing how Dr UYI cast a spell for him and he get his wife back after the spell I was interested I have to do research when I was doing the research I got so many testimony about this same man call Dr UYI how he help people to win lottery how he help people to get there ex back how he help people to do so many things I was happy and I contact him to help me win the lottery when I contact him and he told me what to do and after I did what he ask me to do he den gave me a lottery number to play and told me to go and buy ticket after playing the game I was so surprise the game come out good and I won the sum of 90, 000,000 dollars i was amazed and promise to share it to the people around me if anyone is willing to play the mage lottery it should contact Dr UYI so he can give you the right number to play thanks to you Dr UYI I’m so so grateful contact Dr UYI via drzukalottospelltemple@gmail.com OR WhatsApp on +17174154115

I had to write back and say what an amazing experience I had with Dr Uyi for his powerful lottery spell. My Heart is filled with joy and happiness after he cast the Lottery spell for me, And i won $750,000,000 His spell changed my life into riches, I’m now out of debts and experiencing the most amazing good luck with the lottery after I won a huge amount of money. My life has really changed for good. I won (seventy five thousand dollars)Your Lottery spell is so real and pure. Thank you very much for the lottery spell that changed my life” I am totally grateful for the lottery spell you did for me Dr Uyi and i say i will continue to spread your name all over so people can see what kind of man you are. Anyone in need of help can email Dr Uyi for your own lottery number, because this is the only secret to winning the lottery. Email: (drzukalottospelltemple@gmail.com) OR WhatsApp on +17174154115

Bitcoin Recovery Testimonial

After falling victim to a cryptocurrency scam group, I lost $354,000 worth of USDT. I thought all hope was lost from the experience of losing my hard-earned money to scammers. I was devastated and believed there was no way to recover my funds. Fortunately, I started searching for help to recover my stolen funds and I came across a lot of testimonials online about Capital Crypto Recovery, an agent who helps in recovery of lost bitcoin funds, I contacted Capital Crypto Recover Service, and with their expertise, they successfully traced and recovered my stolen assets.

Their team was professional, kept me updated throughout the process, and demonstrated a deep understanding of blockchain transactions and recovery protocols. They are trusted and very reliable with a 100% successful rate record Recovery bitcoin, I’m grateful for their help and highly recommend their services to anyone seeking assistance with lost crypto.

Contact: Capitalcryptorecover @ zohomail. com

Phone CALL/Text Number: +1 (336) 390-6684

Email: Recoverycapital @ fastservice. com

TANGIBLE INFORMATION ABOUT LOAN PLANNING… THIS HAPPY NEW YEAR..

This is not a normal post that you see every day on the internet where people give fake reviews and false information about excellent financial assistance. I am aware that many of you have been scammed and that fake agents have taken advantage of those seeking loans. I will not call these normal reviews, I will call this situation where I live a witness to how you can get your loan when you meet the company’s requirements. It really does not matter if you have a good credit rating or government approval, all you need is a proper ID card and a valid IBAN number to be able to apply for a loan with an interest rate of 3%. The minimum amount is 1000 euros and the maximum amount that can be borrowed is 100,000,000 euros. I give you a 100% guarantee that you can get your loan through this reliable and honest company, we operate 24 hours online and provide loans to all citizens of Europe and outside Europe. They sent me a document that was checked and tested before I got the loan, so I invite anyone who needs a loan to visit them or contact them via email: michaelgardloanoffice@gmail.com

WhatsApp for Europe: +38591560870

WhatsApp for USA: +1 (717) 826-3251

After you contact them, let them know that Mrs. Dejana Ivica from Zagreb gave you the information. Seeing is believing and you will thank me later when you get a loan from them. I made a promise that after I get a loan from them, I will post the good news to everyone online. If you have friends or relatives, including colleagues, you can tell them about this offer and that it is happening.

BTC expropriation began with hopes of financial growth and prosperity, only to end in devastation when I realized I had fallen victim to a scam, losing a staggering $47,000. The enticing promises of high returns and effortless profits turned out to be nothing more than a cruel deception, leaving me feeling betrayed and distraught. In my darkest hour, I came across Mrs. Lisette Zamora and her recovery firm, who became my guiding light. From our very first interaction, their team demonstrated unmatched professionalism, empathy, and determination to seek justice. With unwavering commitment, they took charge of my case, skillfully navigating the complex legal landscape to recover my stolen funds.

You can contact her via…

Email: zamora~lisette~4~@~gmail~com

WhatsApp: +1—(826)—218—-0536

“In the crypto world, this is great news I want to share. Last year, I fell victim to a scam disguised as a safe investment option. I have invested in crypto trading platforms for about 10yrs thinking I was ensuring myself a retirement income, only to find that all my assets were either frozen, I believed my assets were secure — until I discovered that my BTC funds had been frozen and withdrawals were impossible. It was a devastating moment when I realized I had been scammed, and I thought my Bitcoin was gone forever, Everything changed when a close friend recommended the Capital Crypto Recover Service. Their professionalism, expertise, and dedication enabled me to recover my lost Bitcoin funds back — more than €560.000 DEM to my BTC wallet. What once felt impossible became a reality thanks to their support. If you have lost Bitcoin through scams, hacking, failed withdrawals, or similar challenges, don’t lose hope. I strongly recommend Capital Crypto Recover Service to anyone seeking a reliable and effective solution for recovering any wallet assets. They have a proven track record of successful reputation in recovering lost password assets for their clients and can help you navigate the process of recovering your funds. Don’t let scammers get away with your hard-earned money – contact Email: Recoverycapital @ fastservice. com

Phone CALL/Text Number: +1 (336) 390-6684 Contact: Capitalcryptorecover @ zohomail. com

“In the crypto world, this is great news I want to share. Last year, I fell victim to a scam disguised as a safe investment option. I have invested in crypto trading platforms for about 10yrs thinking I was ensuring myself a retirement income, only to find that all my assets were either frozen, I believed my assets were secure — until I discovered that my BTC funds had been frozen and withdrawals were impossible. It was a devastating moment when I realized I had been scammed, and I thought my Bitcoin was gone forever, Everything changed when a close friend recommended the Capital Crypto Recover Service. Their professionalism, expertise, and dedication enabled me to recover my lost Bitcoin funds back — more than €560.000 DEM to my BTC wallet. What once felt impossible became a reality thanks to their support. If you have lost Bitcoin through scams, hacking, failed withdrawals, or similar challenges, don’t lose hope. I strongly recommend Capital Crypto Recover Service to anyone seeking a reliable and effective solution for recovering any wallet assets. They have a proven track record of successful reputation in recovering lost password assets for their clients and can help you navigate the process of recovering your funds. Don’t let scammers get away with your hard-earned money – contact Email: Recoverycapital @ fastservice. com

Phone CALL/Text Number: +1 (336) 390-6684 Contact: Capitalcryptorecover @ zohomail. com

Website: https://recovercapital.wixsite.com/capital-crypto-rec-1

Special thanks to Henryclarkethicalhacker@gmail.com for exposing my cheating husband. Right with me I got a lot of evidences and proofs that shows that my husband is a f*** boy and as well a cheater ranging from his text messages, call logs, WhatsApp messages, deleted messages and many more, All thanks to Henryclarkethicalhacker @ gmail com , if not for him I will never know what has been going on for a long time. Contact him now and thank me later. Stay safe.

My name is Wendy Taylor, I’m from Los Angeles, i want to announce to you Viewer how Capital Crypto Recover help me to restore my Lost Bitcoin, I invested with a Crypto broker without proper research to know what I was hoarding my hard-earned money into scammers, i lost access to my crypto wallet or had your funds stolen? Don’t worry Capital Crypto Recover is here to help you recover your cryptocurrency with cutting-edge technical expertise, With years of experience in the crypto world, Capital Crypto Recover employs the best latest tools and ethical hacking techniques to help you recover lost assets, unlock hacked accounts, Whether it’s a forgotten password, Capital Crypto Recover has the expertise to help you get your crypto back. a security company service that has a 100% success rate in the recovery of crypto assets, i lost wallet and hacked accounts. I provided them the information they requested and they began their investigation. To my surprise, Capital Crypto Recover was able to trace and recover my crypto assets successfully within 24hours. Thank you for your service in helping me recover my $647,734 worth of crypto funds and I highly recommend their recovery services, they are reliable and a trusted company to any individuals looking to recover lost money. Contact email Capitalcryptorecover@ zohomail. com OR Telegram @Capitalcryptorecover Call/Text Number +1 (336)390-6684 his contact: Recoverycapital@fastservice. com His website: https://recovercapital.wixsite.com/capital-crypto-rec-1

Special thanks to Henryclarkethicalhacker@gmail.com for exposing my cheating husband. Right with me I got a lot of evidences and proofs that shows that my husband is a f*** boy and as well a cheater ranging from his text messages, call logs, WhatsApp messages, deleted messages and many more, All thanks to Henryclarkethicalhacker @ gmail com , if not for him I will never know what has been going on for a long time. Contact him now and thank me later. Stay safe.

gfdsd

I’m pleased to recommend HENRY CLARK a private hacker for any hacking related issues of your interest. I got in contact with him when I was having problems with my cheating husband and needed help in getting evidence against him in court, Henry helped me hack into my husband’s phone and in no time I started seeing his chats and messages, call records including access to his recently deleted conversations… I’m so glad I got in contact with Henry, He is also into various jobs such as Facebook hacking, whats-app hacking, phone hacking, snapchat, Instagram, we-chat, phone text messages, hangouts and so on.. You can contact him by email: HENRYCLARKETHICALHACKER@GMAIL.COM, t, you should contact him today and see for yourself, remember to tell him Sofia referred you.

Do you suspect your spouse of cheating, are you being overly paranoid or seeing signs of infidelity…Then he sure is cheating: I was in that exact same position when I met Henry through my best friend James who helped me hack into my boyfriend’s phone, it was like a miracle when he helped me clone my boyfriend’s phone and I got first-hand information from his phone. Now I get all his incoming and outgoing text messages, emails, call logs, web browsing history, photos and videos, instant messengers(facebook, whatsapp, bbm, IG etc) , GPS locations, phone taps to get live transmissions on all phone conversations. If you need help contact his gmail on , Henryclarkethicalhacker@ gmail com

My name is Wendy Taylor, I’m from Los Angeles, i want to announce to you Viewer how Capital Crypto Recover help me to restore my Lost Bitcoin, I invested with a Crypto broker without proper research to know what I was hoarding my hard-earned money into scammers, i lost access to my crypto wallet or had your funds stolen? Don’t worry Capital Crypto Recover is here to help you recover your cryptocurrency with cutting-edge technical expertise, With years of experience in the crypto world, Capital Crypto Recover employs the best latest tools and ethical hacking techniques to help you recover lost assets, unlock hacked accounts, Whether it’s a forgotten password, Capital Crypto Recover has the expertise to help you get your crypto back. a security company service that has a 100% success rate in the recovery of crypto assets, i lost wallet and hacked accounts. I provided them the information they requested and they began their investigation. To my surprise, Capital Crypto Recover was able to trace and recover my crypto assets successfully within 24hours. Thank you for your service in helping me recover my $647,734 worth of crypto funds and I highly recommend their recovery services, they are reliable and a trusted company to any individuals looking to recover lost money. Contact email Capitalcryptorecover @ zohomail. com OR Telegram @ Capitalcryptorecover Call/Text Number +1 (336)390-6684 his contact: Recoverycapital @ fastservice. com

TRUSTED RECOVERY SERVICE

The most well-known cryptocurrency in the world, Bitcoin, has become extremely popular in recent years. More people and companies are adopting Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies as a form of investment due to their anarchic framework and high return potential. Nevertheless, the emergence of Bitcoin has also given rise to a number of security issues, resulting in instances of lost or unreachable Bitcoins. Consequently, there is an enormous increase in demand for expert Bitcoin recovery services. Ever felt like your heart sinks when you realise you can’t get to your Bitcoin? There is a bigger demand than ever for trustworthy Bitcoin recovery services due to the rising popularity of Bitcoin and other cryptocurrency. The security risks connected with Bitcoin are growing along with its value and use. There are several possibilities for consumers to lose access to their priceless digital assets, including device malfunctions, cyberattacks, and forgotten passwords and wallet seeds. smith white hack service can help in this situation. smith white hack service is the legitimate sidekick when it comes to obtaining your unidentified or unaccessible Bitcoins back. Years of experience and unmatched knowledge have allowed them to assist many people in regaining access to their digital assets. smith white hack service provides specialized solutions that increase your chances of getting your Bitcoins back by analyzing your particular circumstances and using cutting-edge recovery methods. I will suggest your urgent request for support from smith white hack services team through: Do not get left behind. Contact smith white hack service through Email:SMITHWHITEHACKSERVICE@GMAIL COM And also on WhatsApp +1 559 – 508 – 2403

Am so excited to share my testimony of a real spell caster who brought my husband back to me. My husband and I have been married for about 6yrs now. We were happily married with two kids, 3 months ago, I started to notice some strange behavior from him and a few weeks later I found out that my husband is seeing someone else. I became very worried and I needed help. I did all I could to save my marriage but it fail until a friend of mine told me about the wonderful work of Dr Jakuta I contacted him and he assured me that after 24hrs everything will return back to normal, to my greatest surprise my husband came back home and went on his knees was crying begging me for forgiveness I’m so happy right now. Thank you so much Dr Jakuta because ever since then everything has returned back to normal. One message to him today can change your life too for the better. You can contact him via WhatsApp +2349161779461 or Email : doctorjakutaspellcaster24@gmail.com

I was recently scammed out of $53,000 by a fraudulent Bitcoin investment scheme, which added significant stress to my already difficult health issues, as I was also facing cancer surgery expenses. Desperate to recover my funds, I spent hours researching and consulting other victims, which led me to discover the excellent reputation of Capital Crypto Recover, I came across a Google post It was only after spending many hours researching and asking other victims for advice that I discovered Capital Crypto Recovery’s stellar reputation. I decided to contact them because of their successful recovery record and encouraging client testimonials. I had no idea that this would be the pivotal moment in my fight against cryptocurrency theft. Thanks to their expert team, I was able to recover my lost cryptocurrency back. The process was intricate, but Capital Crypto Recovery’s commitment to utilizing the latest technology ensured a successful outcome. I highly recommend their services to anyone who has fallen victim to cryptocurrency fraud. For assistance contact Recoverycapital@fastservice. com and on Telegram OR Call Number: +1 (336)390-6684 via email: Capitalcryptorecover @ zohomail. com you can visit his website:: https://recovercapital.wixsite.com/capital-crypto-rec-1

Am so excited to share my testimony of a real spell caster who brought my husband back to me. My husband and I have been married for about 6yrs now. We were happily married with two kids, 3 months ago, I started to notice some strange behavior from him and a few weeks later I found out that my husband is seeing someone else. I became very worried and I needed help. I did all I could to save my marriage but it fail until a friend of mine told me about the wonderful work of Dr Jakuta I contacted him and he assured me that after 24hrs everything will return back to normal, to my greatest surprise my husband came back home and went on his knees was crying begging me for forgiveness I’m so happy right now. Thank you so much Dr Jakuta because ever since then everything has returned back to normal. One message to him today can change your life too for the better. You can contact him via WhatsApp +2349161779461 or Email : doctorjakutaspellcaster24@gmail. com

FOR CRYPTOCURRENCY RECOVERY, CONTACT TSUTOMU SHIMOMURA

This is the best crypto recovery company I’ve come across, and I’m here to tell you about it. TSUTOMU SHIMOMURA was able to 5:15 PM 30/10/2025 REGHWGHBHH recover my crypto cash from my crypto investment platform’s locked account. TSUTOMU SHIMOMURA just needed 24HRS to restore the $620,000 I had lost in cryptocurrencies. I sincerely appreciate their assistance and competent service. TSUTOMU SHIMOMURA may be relied on since they are dependable and trustworthy. You can also contact them by Email address tsutomushimomurahacker@gmail.com, or WhatsApp +1 (405) 723-3738 and I’m sure you will be happy you did.

HOW I WON THE LOTTERY WITH Drherry LOTTERY SPELL AND MY LIFE CHANGED: I’m a 31-year-old from California and I just won $25 million in the lottery. Life was really hard before this and I was constantly struggling to pay my bills. While searching online for ways to turn things around, I came across stories of people saying that Drherry helped them win the lottery. I was curious and decided to give it a try. I reached out to him and he responded quickly. He told me what was needed to cast a lottery spell. After the spell was done, he gave me numbers to play. I used OLG’s Never Miss a Draw subscription and a few days later, I got a call saying I had won $25 million. I was completely shocked and overwhelmed with emotion. I never believed something like this could happen to me. I am truly grateful to Drherry for this incredible blessing. You can contact him via WhatsApp: +12023654871 or email: DrHerry189@gmail.com

I acquired my first home at the beginning of the year. To some, lottery players appear ridiculous, while we view it as a chance for an improved future. I’m known as Megan Taylor and I have played the lottery for ten years, yet I haven’t won anything substantial. In my pursuit of understanding how to win better, I was advised to consult Lord Meduza the Priest who provided me with the precise 6 numbers that helped me secure the Mega Millions jackpot of $277 million after using his spell powers and following his guidance. Lord Meduza services is top notch and I believe your dreams aren’t finished unless you decide they are. Contact Lord Meduza the Priest and he will assist you in realizing your aspirations.

Email: lordmeduzatemple@hotmail.com

Whats-App +1 (807) 798-3042.

Website: lordmeduzatemple.com

Wow what a good God I am so excited to tell you all how I become a millionaire I’m a woman of faith I was reading a comment on google where I meet a man sharing how (Dr Love Vudu) cast a spell for him and he get his wife back after the spell I was interested I have to do research when I was doing the research I got so many testimony about this same man call (Dr Love Vudu) how he help people to win lottery how he help people to get there ex back how he help people to do so many things I was happy and I contact him to help me win the lottery when I contact him and he told me what to do and after I did what he ask me to do he den gave me a lottery number to play and told me to go and buy ticket after playing the game I was so surprise the game come out good and I won the sum of 90, 000,000 dollars i was amazed and promise to share it to the people around me if anyone is willing to play the mage lottery it should contact (Dr Love Vudu ) so he can give you the right number to play thanks to you (Dr Love Vudu ) I’m so so grateful contact (Dr Love Vudu) via drlovevudu@gmail.com OR WhatsApp on +12023081978

FRESH FULLZ UPDATED-2026 AVAILABLE

USA UK CANADA GERMANY SPAIN ITALY AUSTRALIA

Tax Return 2026 Filling Fullz

Children Fullz 2011-2023

Young & Old Age Fullz 1930-2009

High Credit Score 700+ Scores

DL & ID Photos Front Back with selfie

DL Photos available all countries

Passport Photos

W-2 Forms with DL Photo (2021-22-23)

USA LLC Docs with DL & SSN

USA-> Name SSN DOB DL Address City State Zip Phone Email Employee & Bank Info

UK-> Name NIN DOB DL Address City State Postcode MMN Account number Sort Code

Canada-> Name SIN DOB DL Address City State Zip Phone MMN

Many Other Countries Fresh Fullz available in Bulk quantity

All Info will be provided with guarantee

Tax Filling Tools & Tutorials available

Our Team Is working 24/7 & here we’re:

————————————–

Telegram@killhacks – @ leadsupplier

What’s App – (+1) 727”’788”’6129

Telegram Channel – t.me/leadsproviderworldwide

Discord – @ leads.seller

VK Messenger – @ leadsupplier

Signal – @ killhacks.90

Email – hacksp007 at gmail dot com

Zangi – 17-7369-4210

Email Leads & phone number Leads

Crypto, Forex, Investors Leads

Payday & Loan Leads

Doctors Database, Health & Medical Leads

Car Database with Reg Numbers

Email & Pass Combos

Office365 Leads & Logins

Crypto Exchanges Leads

LinkedIn, Facebook, Instagram Leads

Education & School Leads

TOOLS & TUTORIALS AVAILABLE

H@cking Sp@mming C@rding Sc@M Pages Scripting Tools

Complete packages for Sp@mming & Ph!shing Attack

Sqli Injectors & Pen3tratrion Tools with tutorials

SMTP Linux Root & Sc@m Page Scripting

C@rding Tools & Tutorials (For CC|CVV Cash out & Dumps)

We are also providing complete packages for the above listed stuff

Complete guidance & assistance will be provided

Just try our services, we’ll give your best

#fullz #usafullz #canadafullz #ukfullz #taxreturn2026 #usataxreturn #dlphotos

#personalID #leads #taxfillingfullz #usataxfilling #childrenfullz #trumpiran #indiarussia

#chinausa #usachina #MAGA #Btc #btcbullrun #cryptocrash #cryptobill #eth #altseason

*Be aware from the scammers using our cloned names

I can’t believe this. A great testimony that i must share to all HERPES patient in the world i never believed that there could be any complete cure for HERPES or any cure for HERPES at all. I saw people’s testimony on blog sites of how DR Ahonsie prepared herbal cure and brought them back to life again. i had to try it too and you can’t believe that in just few weeks i started using it all my pains stop gradually and I was completely cured with the treatment the doctor gave to me. Right now i can tell you that few months later on now i have not had any pain. Delay in treatment leads to death. Here is his email: drahonsie00@gmail.com message him on Whatsapp +2348039482367 https://drahonsie002.wixsite.com/dr-ahonsie

Are you looking for financial freedom? Are you in debt, do you need a loan to start a new business? Are you financially broke, Do you need a loan to buy a car or a house? Are you turning down your local bank to get financing? Do you want to improve your finances? Do you need a loan to pay off your bills? Search no more, we welcome you to get all types of loans for you at a very affordable interest rate of 2% For more information, contact us now by Email; Susanne_Klatten21@outlook.com, WhatsApp : +1 812,,380..0994

Please write back if interested.

Full name:

Sex:

Marital status:

Address:

Country:

City:

Occupation:

Monthly income:

Zip code:

Amount:

Loan duration:

Mobile phone number

Do you speak English:

Susanne Klatten

A testimony that saved my marriage by the great psychic priest lady Milly +27634900172

I want to testify to everyone on how my husband and i got children after our 5years of marriage. we got married and we could not conceive a child we have been to several hospitals for checking and the doctors always say that we are okay that nothing is wrong with us, we have been hoping for a child, my husband was beginning to keep late night outside and pressure from the family for him to marry another wife and divorce me, i was always crying and weeping because i was loosing my marriage. so i talked to one of my friends and one of them told me that she also have been through this same situation but she got her help of getting her own child from a great psychic spells priest of fertility, so she told me that she will connect me to the priest and she will do some fertility spell for me to have my own child, i contacted this great priest and she said i should bring all my information to her and she said in 2days after the spell will be completed. so i waited and i went back made love with my husband and i conceive. so i am very grateful to the priest for her help and miracle that help me save my marriage. please for same help, contact her on +27634900172

We were told that crypto was the next big thing and many people fell victim into the wrong hands and i was also one of them, i was told to invest and get 10% of my investment every month and it was looking all good at first because i got 10% the first month and i was persuaded to invest more which i did, the second month came expecting the next 10% then i was told to send my bitcoin barcode which i did the next thing i discovered that my bitcoin wallet was cleaned up, i was left devastated and lost, to crown it up the people i invested in stopped replying and all of these happened on telegram, i came across macprivateinvestigators@gmail.com and they helped recover all my stolen funds along side with the investment.

TSUTOMU SHIMOMURA IS BEST HACKER

WARNING: Scammers will stop at nothing to steal your hard-earned money! But, I’m living proof that TSUTOMU SHIMOMURA can help you RECLAIM YOUR LOST FUNDS! I thought I’d lost my life savings of $58,000 after investing with a fake broker, promising me a whopping $187,000 profit to fund my urgent surgery. But, TSUTOMU SHIMOMURA did not give up on me. They worked tirelessly to track down my money and recover it. And, after months of intense effort, they successfully recovered my entire investment – $58,000! I’m now able to focus on my health and recovery, knowing that I’ve been given a second chance thanks to TSUTOMU SHIMOMURA Don’t let scammers ruin your life like they almost did mine! If you’re in a similar situation, don’t hesitate to reach out to TSUTOMU SHIMOMURA. They’ll be your champion in the fight against online fraud!” be happy you did. You can also contact them by Email address tsutomushimomurahacker@gmail.com, or WhatsApp +1 (806) 283-5031 Telegram +1 (803) 632-0791

After being in relationship with him for seven years, he broke up with me, I did everything possible to bring him back but all was in vain. I wanted him back so much because of the love I have for him and I begged him with everything, I made promises but he refused. I contacted a spell caster called DR ISIKOLO that could help me cast a spell to bring him back but I am the type that never believed in spell, I had no choice than to try it, I mailed the spell caster, and he told me there was no problem that everything will be okay before two days, that my ex will return to me before three days, he cast the spell and surprisingly in the second day, it was around 4pm. My ex called me and we resolved the differences and we are happy together now. Anybody could need the help of the spell caster and you can review his website: https://isikolo-temple.com or call/text him on WhatsApp : +2348133261196.

I want to take a moment to sincerely thank FAST WEB HACKERS and their team for their outstanding service. They successfully helped me recover my stolen cryptocurrency worth $150,000 after it was taken through a fraudulent online investment. At first, I was skeptical, but their professionalism, transparency, and technical expertise quickly built my trust. They handled the process efficiently and delivered exactly as promised. I’m genuinely grateful for their help and the relief of getting my funds back. If you ever find yourself in a similar situation, you can contact them via Email: fastwebhackers@gmail. com/ fastwebhackers@aol. com or visit their Telegram: t.me/@fastwebhackers

I lost my marriage after 2 years and it was a horrible experience for me. My wife left me and my son and everything happened beyond my control and I never knew few people around me engineered my wife and turned her against me just because I choose to build my family and focus more on it. I had to seek help because I know I did not do anything to have my marriage crashed. Dr OGBO helped me and a lot was revealed to me on what transpired. He cast a love reunion spell that bonded my wife and I back together and the whole evil my family did against me was revealed. Am thankful that my home is back more happier than ever and all the appreciation goes to Dr OGBO as he indeed fixed my problems just after 48 hours. Review /contact him on his page: psychicogboreading@gmail.com or text him on WhatsApp +2349057657558.///

A breach of my cyber privacy led to the loss of my digital assets, including Bitcoin valued at over $120,000. Hackers were able to clone my email and gain access to my seed phrase, which they used to drain my assets. The experience was infuriating and overwhelming.

Fortunately, a friend referred me to Morphohack Cyber Service, a data and funds recovery firm. Their team successfully helped me recover every dollar and also assisted in securing my digital environment against future threats. Their professionalism and expertise were truly impressive.

I highly recommend Morphohack Cyber Service to anyone facing similar issues. They specialize in recovering crypto, Bitcoin, private data, hacked accounts, and lost files. You can contact them safely via email for any inquiries. (Morphohack@cyberservices.com)

I am victim of a Cryptocurrency Exchange called “UBS Cryptocurrency Exchange” probably based in Hong Kong, which is renamed as “CREDIT SUISSE Cryptocurrency Exchange” in September 2024. I lost 485,700 USDT by investing and trading in this platform since November 2025. The exchange is not allowing me to withdraw my wallet funds and keeps on asking to pay various kinds of fees like tax, membership fee, account reactivation fee, network channel fee, UBS Bank saving account opening fee, card fee, withdrawal fee, etc. In spite of paying all the fees I am not able to withdraw my wallet funds. The last transaction of deposit of network fee of 5000 USDT was made on 16th August 2024. My present wallet amount is 1,560,586 USDT.

Most of my investment for trading in the above exchange and paying their fees comes from loans from various Indian banks. I became completely broke and barely manage to survive with very little money. In a desperate attempt to recover my funds I approached a recovery firm based in USA called Mr Dannie Expert which scammed me for about $5000. Then their ex-employee contacted me and he again scammed me for about $1900. I naively trusted them because I was desperate. However after few more attempts for a way to recover my funds I found JHADDIX ETHICAL HACKER’S a referral through my friend and I located their physical office in New York and they were able to completely retrieve my stolen digital assets within few hours I contacted them. This funds came back to my wallets in tranches and rescued me from depression. What I thought was impossible became possible right before me.

Are you currently in a similar situation of losing money to scammer or you have issues with your crypto wallets? Speedily send a mail to : jhaddixethicalhacker@gmail.com

RECOVER YOUR LOST CRYPTO ASSETS & IMPROVE YOUR CREDIT SCORE WITH ASORE HACK INTELLIGENCE. NO UPFRONT PAYMENT REQUIRED.

Asore Corp. is a team of Cyber Intelligence, Crypto Investigation, Asset Tracing and ethical hacking experts. Working together to form a private cyber and crypto intelligence group focused on providing results.

Using the latest Cyber Tools, Open Source Intelligence (OSINT), Human Intelligence (HUMINT), and cutting edge technology, we provide actionable intelligence to our clients.

WHY CHOOSE US?

– Expert Cyber Investigation Services —Our cyber investigators operate professionally and anonymously to crack all firewalls known to man.

– Cryptocurrency And Digital Asset Tracking — We are able to track the movement of different crypto currencies and assets. If the asset has been moved, we are able to follow it.

– Strategic Intelligence For Asset Recovery — The first step to recovery is locating recoverable assets. Our experienced team will be able to walk you through the process.

Schedule a mail session with our team of professionals today via – asorehackcorp (@) gmail (.) com to get started immediately.

BEWARE of FABRICATED reviews and testimonies endorsing tricksters, do not get scammed twice.

Disclaimer: Asore Corp. is not a law enforcement agency and not a law firm. Like all legitimate private investigators, we can guarantee specific results. We apply our expertise and resources to every case professionally and ethically…….

I have had my fair share of emotional traumas and failed relationships. There is nothing more to life than staying hopeful even when we expect the worse. I was lucky once more when i met my fiancé and he was all that i ever wanted in a man. I was always treated right by him and i had always believed we are ending up together. Unknown to me that devil had struck even before my wishes came through. He was taken from me by another bitch and it was hell for me knowing he had left me. I was so sure that he didn’t do so with his clear mind because everything seems award when it occurred. So i had to look for help and I found dr isikolo who revealed to me that my man was hypnotized with charms by the said lady. He worked for me and got my man back to me and now we are back again. I cant be thankful enough knowing everything Dr isikolo promised was fulfilled and knowing the result of his works manifests after 48 hours. No lies about all you will ever hear about him and what he does. Contact him now if need be and be fully assured he wont fail you. Text him on WhatsApp via +2348133261196, or visit his webpage: https://isikolo-temple.com

GENUINE HACKER FOR HIRE CONSULT JAYWEB RECOVERY EXPERT

If you have lost your bitcoins and are feeling hopeless, I highly recommend Jayweb Bitcoin Recovery. I was in a tough situation after I had lost my bitcoin and thought my money was gone forever. I’m delighted that I decided to test Jayweb. They helped me get my bitcoins back. They kept me informed at every turn, and the procedure was straightforward. It is strongly advised that you get in touch with them if you are experiencing a similar issue.

WhatsApp: +1 (305) 452-9075

Email: jay.webb.hack@mail.com

Hello my name is Kallya from USA i want to tell the world about the great and mighty spell caster called Priest Ade my husband was cheating on me and no longer committed to me and our kids when i asked him what the problem was he told me he has fell out of love for me and wanted a divorce i was so heart broken i cried all day and night but he left home i was looking for something online when i saw an article how the great and powerful Priest Ade have helped so many in similar situation like mine he email address was there so i sent him an email telling him about my problem he told me he shall return back to me within 24hrs i did everything he asked me to do the nest day to my greatest surprise my husband came back home and was crying and begging for me to forgive and accept him back he can also help you contact ancientspiritspellcast@gmail.com

Website ancientspellcast.wordpress.com WhatsApp: +2347070518515

FOR CRYPTOCURRENCY RECOVERY, CONTACT TSUTOMU SHIMOMURA

This is the best crypto recovery company I’ve come across, and I’m here to tell you about it. TSUTOMU SHIMOMURA was able to 5:15 PM 30/11/2025 RIGHT GHH recover my crypto cash from my crypto investment platform’s locked account. TSUTOMU SHIMOMURA just needed 24HRS to restore the $620,000 I had lost in cryptocurrencies. I sincerely appreciate their assistance and competent service. TSUTOMU SHIMOMURA may be relied on since they are dependable and trustworthy. You can also contact them via Email: tsutomushimomurahacker@gmail.com Or WhatsApp +1 (806) 283-5031 Telegram +1 (803) 632-0791 and I’m sure you will be happy you did.

Testimonials & Reviews of a real spell caster, It is amazing how quickly Dr. Excellent brought my husband back to me. My name is Heather Delaney. I married the love of my life Riley on 10/02/15 and we now have two beautiful girls Abby & Erin, who are conjoined twins, that were born 07/24/16. My husband left me and moved to be with another woman. I felt my life was over and my kids thought they would never see their father again. I tried to be strong just for the kids but I could not control the pains that tormented my heart, my heart was filled with sorrows and pains because I was really in love with my husband. I have tried many options but he did not come back, until i met a friend that directed me to Dr. Excellent a spell caster, who helped me to bring back my husband after 11hours. Me and my husband are living happily together again, This man is powerful, contact Dr. Excellent if you are passing through any difficulty in life or having troubles in your marriage or relationship, he is capable of making things right for you. Don’t miss out on the opportunity to work with the best spell caster. Here his contact. Call/WhatsApp him at: +2348084273514 “Or email him at: Excellentspellcaster@gmail.com